Reducing amputations through a coordinated limb salvage program

The following story is an example of a coordinated approach to limb salvage instituted at Sanger Heart and Vascular Institute in Charlotte, North Carolina.

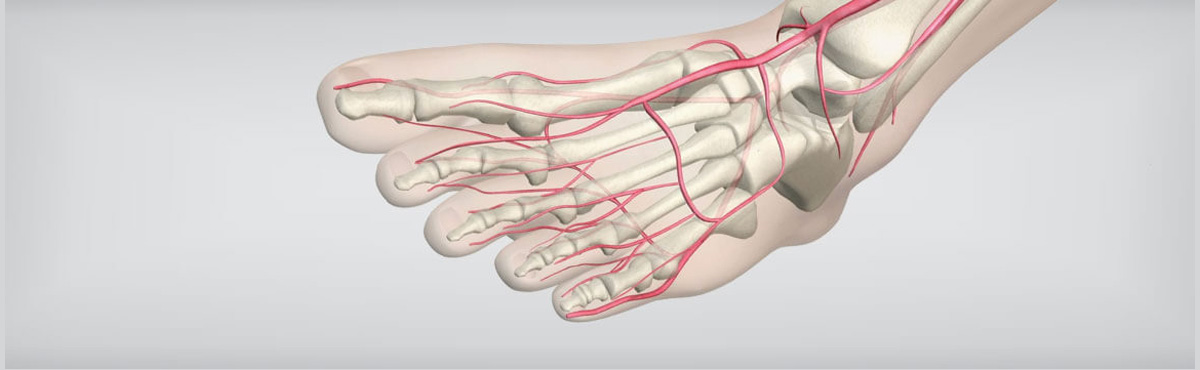

One of the most devastating consequences of advanced peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is critical limb ischemia (CLI), a severe blockage of the arteries that reduces blood flow to the extremities. CLI results in severe pain, skin ulcers, and, if left untreated, gangrene.

Unfortunately, the first line of treatment is often below-the-knee (BTK) or above-the-knee (ATK) amputation. While amputation may sometimes be the best option for the patient, it is important that the physician conduct a vascular workup beforehand to ensure an endovascular procedure isn’t a viable alternative.

Tracking total amputation rates due to diabetes and/or PAD in the general population has proven to be difficult. Reports have shown a 23% increase in amputation rates in the diabetic population since 19881 with a total annual cost of approximately $8.3 billion, not including prosthetic or rehabilitation costs2. Studies have shown that the total lifetime healthcare costs for an amputee is more than $500,000 per person, which is double the lifetime medical cost for the average person3,4. When you consider the high 5-year mortality associated with amputations, this number is even more staggering.

In addition to the high costs, there is a clear trend for recurrence of amputations, and the mortality rates within one year of CLI diagnosis and amputation in the Medicare population is 40.42%5.

Many interventionalists “consider endovascular treatment of CLI ‘voodoo medicine,’” explained Dr. Christopher Boyes, vascular surgeon at Sanger Heart & Vascular Institute in Charlotte, North Carolina. “When did it become accepted that an amputation is the ‘safe’ option for patients with CLI?”

According to Dr. Boyes, there are several factors that have led to this drastic standard of care. But, he said, with education, training, and a new CLI treatment algorithm, endovascular interventions could become the accepted first line of therapy.

But, it’s not all about patency rates. “It’s important to note that focusing solely on the intervention and not the external variables that account for limb salvage is a mistake,” he said. “We must take a multidisciplinary approach to limb salvage.”

The Sanger limb salvage program was started two years ago and focuses on points of entry, which include podiatrists, wound-care physicians, vascular surgeons, orthopedists, and emergency room staff who are often the first to see patients with CLI symptoms. Testing for these patients should include measuring toe brachial index (the ratio between toe pressure and the highest of the two brachial pressures) and HbA1c levels (used to diagnose diabetes and prediabetes).

If patients present with nonhealing wounds, they should be referred to a vascular specialist as soon as possible. “The earlier the treatment, the better the chances are for limb salvage,” Dr. Boyes said.

Following an endovascular procedure, patients should be educated about follow-up care, including the importance of wearing proper socks and shoes, orthotic care, and risk-factor modification, such as antiplatelets, statins, smoking cessation, diabetic control, and checking feet for reoccurrence of the wound.

To ensure the process is sufficiently managed, the limb salvage program needs to be viewed as a team effort with a navigator coordinating the process to ensure the team stays on the same page.

“Communication is key to improving the process, from beginning to end,” Dr. Boyes said. “Through better standards and reporting processes, we hope that a collaborative approach to the management of CLI and amputation prevention will become the new standard of care within the next five years.”